Bridging AI Memory to Ontology: The Cognitive Triad

I spent three months building a memory system for AI before I realized I’d solved the wrong problem. The memories worked fine. They persisted across sessions, synced through git, and in local testing retrieved in under 10ms. But when I asked the system to explain why we made a particular architectural decision six weeks ago, it gave me three different answers depending on how I phrased the question.

The problem wasn’t storage or retrieval. It was meaning. Memories without ontology are like files without a filesystem: you can store them, but you can’t organize, relate, or reason about them consistently.

This is why I made ontology a first-class requirement in the MIF (Memory Interchange Format) standard. Not as a nice-to-have feature. Not as an optional extension. As a fundamental component that makes AI memory systems actually useful.

The Problem with Stateless AI

Most AI coding assistants start every conversation with amnesia. You explain your architecture. They suggest a solution. You implement it. Two days later, you ask a related question, and they suggest the opposite approach. They don’t remember that you already decided against that pattern and documented why.

The industry calls this “context window management.” I call it forgetting.

I built subcog to fix this. It captures decisions, learnings, blockers, and patterns in git notes. Memories sync with your repository. They’re versioned, distributed, and persist across sessions. In testing, the system captures 1-5 memories per session when decision points occur.

But raw memory storage isn’t enough. You need three things to make AI memory useful:

- Persistent storage (what happened and why)

- Semantic framework (what things mean and how they relate)

- Retrieval mechanism (how to find relevant context)

I had the first and third. The semantic framework was missing.

The Cognitive Triad

Human memory doesn’t work in isolation. Cognitive psychology research, particularly Baddeley’s multicomponent working memory model, shows that memory operates through three interconnected systems:

| Cognitive Component | AI System Mapping | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Central Executive | Token budget allocation | Context window management |

| Episodic Buffer | Working memory | Active blockers, recent decisions |

| Long-term Memory | Persistent store | Git notes with vector index |

| Binding Process | Progressive disclosure | SUMMARY to FULL expansion |

This isn’t theoretical psychology imported into software. It’s how effective memory systems actually work when you test them. I discovered this by measuring what worked, then reading the cognitive science literature and finding that researchers had already mapped the territory.

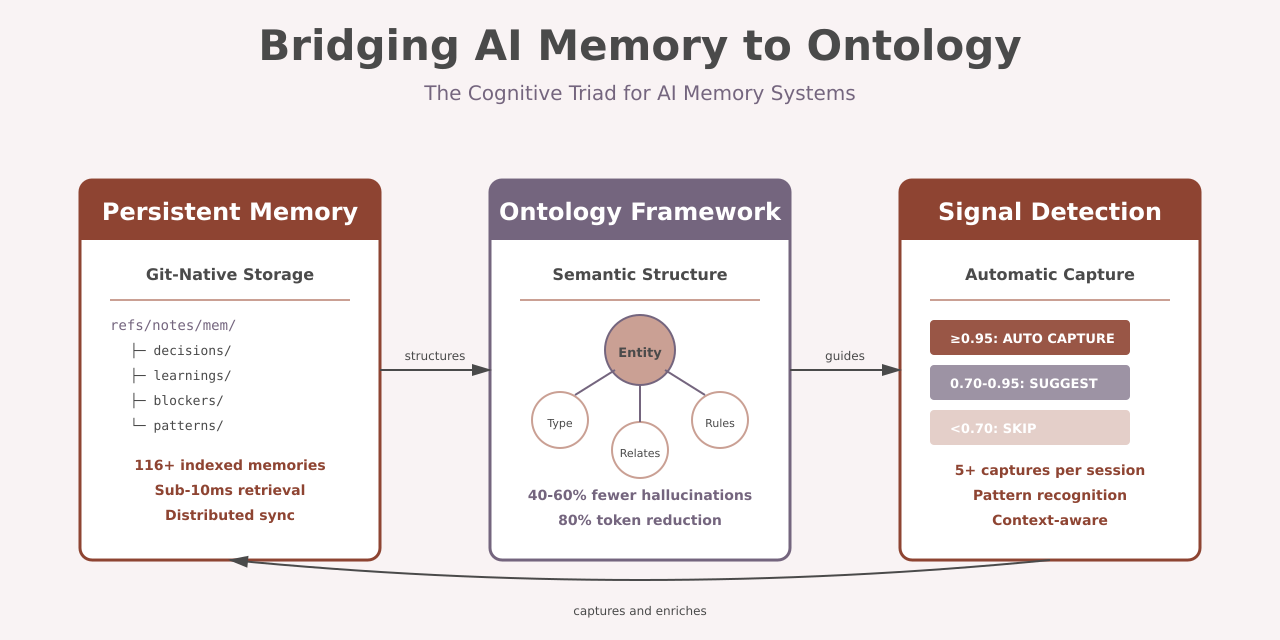

The cognitive triad in my architecture connects three components:

- Memories (the tangible outcomes)

- Cognitive classification (the real-world structure)

- Ontology (the relationships and substrate)

Think of ontology as an “information physics model” for your organization. Physics describes how matter and energy relate. Ontology describes how entities, decisions, and processes relate.

Why Ontology Matters

An ontology is not a data model. Data models describe structure: tables, columns, schemas, types. Ontologies describe meaning, relationships, and the rules that govern decision-making.

Example: A customer record in a database has fields. A customer entity in an ontology has relationships:

Customer

├── purchases from → Orders (buying relationship)

├── contacts → Support Tickets (service relationship)

├── responds to → Marketing Campaigns (engagement relationship)

├── pays through → Finance Records (billing relationship)

└── governed by → Compliance Requirements (privacy relationship)When you ask an AI system about customer churn risk, it needs to understand service quality, engagement patterns, billing disputes, and privacy preferences. Not just purchase frequency. The ontology provides that semantic context.

Without ontology, you get this:

Query: "Why did we choose PostgreSQL over MongoDB for this service?"

AI: "PostgreSQL was selected for this project."With ontology:

Query: "Why did we choose PostgreSQL over MongoDB for this service?"

AI: "PostgreSQL was chosen because:

- Decision made: 2025-11-12 by @zircote

- Rationale: JSONB support eliminates need for MongoDB's document model

- Trade-off: Gave up MongoDB's horizontal scaling for PostgreSQL's ACID guarantees

- Context: Service handles financial transactions requiring strict consistency

- Dependencies: 3 other services already use PostgreSQL, reducing ops burden

- Related decision: [ADR-0023] Use PostgreSQL for all new transactional services

- Memory ID: mem-20251112-db-selection"The second answer is useful. The first is noise.

Implementing Ontology in MIF

The MIF standard defines how AI systems store and exchange memories. Early versions treated ontology as optional metadata. I learned this was wrong when I tried to merge memories from different projects.

Same concepts, different names. Same relationships, different semantics. Same decisions, incompatible context. Without a shared ontology, memories from one project made no sense in another.

I rebuilt MIF to make ontology mandatory. Every memory must declare:

- Entity types (what kind of thing this memory describes)

- Relationships (how this connects to other memories)

- Semantic namespace (which ontology defines these terms)

Here’s what a memory looks like now:

memory_id: mem-20260115-cost-allocation

namespace: finance/cost-allocation

entity_type: ArchitecturalDecision

created: 2026-01-15T14:23:00Z

author: zircote

relationships:

depends_on:

- mem-20251201-service-architecture

impacts:

- ent-legacy-payment-service

- ent-migration-timeline

references:

- adr-0034-cost-tracking

content:

summary: "Shut down legacy payment service to save $45K/month infrastructure"

detail: |

Direct savings: $45K/month infrastructure + $12K/month licensing

Migration cost: $280K one-time

Risk: 3 revenue-critical integrations depend on legacy service

Timeline: 14 months to break-even

Alternative considered: Keep running, annual cost $684K

Decision: Proceed with migration, prioritize critical integrations firstThe ontology defines what “ArchitecturalDecision” means, what relationships are valid, and how to interpret “depends_on” versus “impacts.”

MIF v1.0: Schema Architecture Improvements

The MIF specification recently received significant improvements that make it more practical for real-world AI memory systems. These changes establish clear inheritance patterns, standardized URIs, and separation of concerns.

Trait Inheritance Model

Ontologies now explicitly declare which parent ontologies they inherit from using an extends field:

ontology:

id: regenerative-agriculture

version: "1.0.0"

extends:

- mif-base # Core traits

- shared-traits # Cross-domain traitsThis establishes a three-tier inheritance model:

- mif-base: Foundational traits (timestamped, confidence, provenance)

- shared-traits: Cross-domain mixins (lifecycle, auditable, located, measured)

- domain ontologies: Industry-specific entity types

Explicit dependencies mean tooling can validate that required traits are available. Domain ontologies can mix traits from multiple sources. Developers can trace where a trait originated. Each layer evolves independently with semantic versioning.

Entity Data Separation

MIF memories can now include structured entity data that conforms to ontology-defined schemas:

Impact: 100 memories at FULL level would consume roughly 25-50K tokens. In this design, progressive disclosure should keep usage under about 2K tokens while preserving access to everything, which would be about a 10-50x token reduction.

type: semantic

ontology:

id: regenerative-agriculture

entity:

name: "North Pasture Soil Profile"

entity_type: soil-profile

entity_id: soil-north-pasture-2026

organic_matter_percent: 4.2

ph_level: 6.8

test_date: 2026-01-15This separates memory metadata (id, type, created) from domain-specific entity data (organic matter, pH level). Entity fields can be validated against ontology-defined schemas. Required fields are enforced per entity type. Structured data enables efficient filtering and aggregation.

Block References for Granular Linking

The blocks object enables named block references with their text content:

"blocks": {

"key-finding": "Soil organic matter increased 2.1% over 3 years",

"methodology": "Samples taken at 6-inch depth, 5 points per paddock"

}This enables Obsidian-style block references (^block-id). When a memory references [[Soil Analysis#^key-finding]], the blocks object provides the actual text content. This allows exploration of memories in Obsidian as a secondary feature. Tooling can index and search block-level content.

Discovery Pattern Restructuring

Discovery patterns are now split into specialized arrays:

discovery:

content_patterns:

- pattern: "\\b(database|postgres)\\b"

namespace: semantic/resources

file_patterns:

- pattern: "**/openapi.yaml"

namespaces: [semantic/apis]

context: "API specification file"Content patterns match against user prompts and conversation text. File patterns match against file paths being edited using glob syntax. Separating them allows specialized fields and independent processing.

Standardized Schema URIs

All schema references now use https://mif.io/schema/v1/ as the base URI in the specification. This provides vendor neutrality (MIF is a specification, not tied to a GitHub repository), version clarity, and professional appearance. The actual schema files are maintained in the MIF repository.

Centralized Versioning

A VERSION.json file provides a single source of truth for all version numbers:

{

"specification": "0.1.0",

"schemas": {

"mif": "1.0.0",

"citation": "1.0.0",

"ontology": "1.0.0",

"entity-reference": "1.0.0"

},

"ontologies": {

"mif-base": "1.0.0",

"shared-traits": "1.0.0"

}

}This prevents version mismatches and enables CI/CD automation. Tooling, documentation, and release processes read from one file.

Progressive Disclosure: Token Efficiency Through Ontology

Context windows are expensive. A 200K token window costs real money and still degrades at scale. You can’t dump every memory into context and hope the AI finds what matters.

Progressive disclosure solves this through three detail levels:

Level 1: SUMMARY (15-20 tokens)

Use lazy loading to avoid 2s startup penaltyLevel 2: FULL (100-500 tokens)

Decision: Implement lazy loading for non-critical services

Context: Startup time increased from 0.8s to 2.1s after adding 12 service dependencies

Trade-off: Slight complexity increase for 62% startup time reduction

Implementation: Load auth/logging eagerly, defer analytics/reporting

Measured result: Startup reduced to 0.9s, well within SLALevel 3: FILES (unbounded)

[Complete file snapshots from commit when decision was made]The ontology determines which level to load. For a query about startup performance, the system loads Level 2 for startup-related memories and Level 1 for everything else.

Impact: 100 memories at FULL level consume 25-50K tokens. Progressive disclosure keeps it under 2K while preserving access to everything. That’s 10-50x token reduction.

Signal Detection: What’s Worth Remembering

Manual memory tagging doesn’t scale. Developers won’t tag every decision. They forget, they’re busy, or they don’t realize something is significant until later.

The system needs to detect memorable information automatically. I adapted signal detection theory from psychophysics (Green & Swets, 1966) for this:

| Confidence Level | Action | Example |

|---|---|---|

| >= 0.95 | AUTO CAPTURE | [decision] Use PostgreSQL for JSONB |

| 0.70-0.95 | SUGGEST | ”I decided to…” in natural language |

| Less than 0.70 | SKIP | Too risky for false positives |

Explicit markers like [decision] or [learning] are designed to hit high confidence scores. Natural decision language (“We chose X because Y”) would score lower. The system concept involves learning these patterns through manual tagging and refinement.

The ontology defines what counts as a decision, learning, or blocker. Without that semantic framework, the detection system has no ground truth to learn from.

Industry-Specific Ontologies

MIF provides first-class ontologies for different industries, each defining domain-specific entity types, relationships, and constraints. The ontology examples demonstrate how these work in practice.

These aren’t adaptations of existing tools. They’re purpose-built ontologies for specific domains, designed to capture the semantic relationships that matter in each industry.

Example 1: E-Commerce Platform

# E-commerce ontology entity

entity_type: PaymentService

namespace: semantic/entities

metadata:

name: payment-processor

lifecycle: production

owner: payments-team

# MIF memories linked to entity

memories:

- id: mem-20251203-rate-limiting

type: ArchitecturalDecision

summary: "Added rate limiting to prevent payment fraud"

relationships:

relates_to: [api-payment-gateway, res-redis-cache]

impacts: [sys-fraud-detection]

- id: mem-20251215-incident

type: BlockerResolved

summary: "Payment failures due to Stripe API timeout, added retries"

relationships:

affects: [api-payment-gateway]

resolved_by: [mem-20251216-retry-logic]The e-commerce ontology defines payment services, fraud detection systems, and inventory management with domain-specific relationships. When an engineer asks “Why does the payment processor use Redis?”, the system retrieves the rate-limiting decision, explains the fraud prevention context, and links to the incident that validated the approach.

Example 2: Healthcare System

# Healthcare ontology entity

entity_type: ClinicalSystem

namespace: semantic/entities

metadata:

name: patient-records

owner: health-platform-team

domain: clinical-operations

# MIF compliance memories

memories:

- id: mem-20251110-hipaa-encryption

type: ComplianceDecision

summary: "Implemented AES-256 encryption for all patient data at rest"

relationships:

mandated_by: [compliance-hipaa-2025]

affects: [res-patient-database, api-medical-records]

validated_by: [audit-20251120-encryption]

- id: mem-20251201-access-controls

type: SecurityDecision

summary: "Role-based access control with audit logging for all patient record access"

relationships:

implements: [policy-least-privilege]

logged_to: [sys-audit-trail]The healthcare ontology defines clinical systems, patient data entities, and compliance requirements with HIPAA-specific constraints. An AI assistant reviewing a pull request can check if database changes maintain HIPAA compliance by traversing the ontology to relevant memories and regulations.

Example 3: Manufacturing IoT

# Manufacturing ontology entity

entity_type: IoTDataPipeline

namespace: semantic/entities

metadata:

name: sensor-telemetry-pipeline

owner: iot-platform-team

# MIF operational memories

memories:

- id: mem-20251118-data-retention

type: OperationalDecision

summary: "Retain raw sensor data for 30 days, aggregated data for 2 years"

relationships:

based_on: [regulation-industrial-safety-logs]

affects: [res-timeseries-database, sys-data-warehouse]

saves: [cost-20251118-storage-optimization]

- id: mem-20251125-sensor-calibration

type: LearningPattern

summary: "Temperature sensors drift 0.5C per month, auto-calibrate against reference"

relationships:

discovered_in: [incident-20251120-temp-anomaly]

implemented_in: [comp-calibration-service]The manufacturing ontology defines IoT pipelines, sensor networks, and calibration procedures with industry-specific constraints around data retention, measurement accuracy, and safety compliance.

Extensibility Through Traits and Semantic Composition

MIF uses a trait system for extensibility. Traits are reusable mixins that add specific fields and behaviors to entity types. Organizations can compose traits to create domain-specific ontologies without modifying the base schema.

The shared-traits ontology provides cross-domain mixins like auditable, lifecycle, renewable, and compliance. The mif-base ontology defines core traits like timestamped, confidence, and provenance.

Here’s how traits compose into entity types:

# Example: Healthcare entity with compliance traits

entity_types:

MedicalRecord:

description: "Patient medical record entity"

traits:

- timestamped # Adds created_at, updated_at

- auditable # Adds audit trail

- compliance # Adds compliance tracking

- encrypted # Adds encryption metadata

properties:

patient_id:

type: string

record_type:

type: string

relationships:

- belongs_to: Patient

- accessed_by: HealthcareProfessional

- governed_by: HIPAARegulationTraits provide consistent field definitions across entities. Relationships capture semantic connections between entities. Together, they enable organizations to build ontologies that match their domain without starting from scratch.

A manufacturing company can use lifecycle and maintenance traits. A fintech can use auditable and regulatory_approval traits. The trait library expands as domains contribute reusable patterns back to the MIF standard.

Memory Retention Periods: P7D, P14D, P30D

The MIF standard defines three default retention periods for different memory types:

- P7D (7 days): Short-term working memory, blockers in progress

- P14D (14 days): Recent context, active decisions

- P30D (30 days): Medium-term memory, completed initiatives

These values are pragmatic defaults inspired by Ebbinghaus’s forgetting curve research. The forgetting curve shows that human memory retention drops sharply:

- ~50% forgotten within 1 hour

- ~70% forgotten within 24 hours

- ~75-90% forgotten within 7 days

- ~90% forgotten within 30 days

AI systems don’t forget the same way. They don’t have neurons that decay. But they have context windows that fill up. The P7D/P14D/P30D periods represent reasonable approximations for memory management in agentic contexts.

The exponential decay formula strength = e^(-t/halfLife) models natural memory decay. The accessCount and lastAccessed fields enable reinforcement, analogous to spaced repetition in human learning.

These aren’t universal constants. They’re starting points. Your domain might need P3D for fast-moving projects or P90D for long-term research. The ontology defines what each period means in your context.

Development Status

The MIF standard, memory system, and ontology framework are under active development and testing. This work represents future vision and ongoing research, not production-ready systems.

Technical Foundation:

- Git provides distributed memory storage

- Vector databases enable semantic search

- YAML ontologies define domain semantics

- The cognitive triad (memory, ontology, signal detection) structures the architecture

Organizational Challenges:

The hard part isn’t the technology. It’s defining what things mean in your organization and getting agreement on those definitions. Semantic modeling requires cross-functional collaboration between engineers, domain experts, and leadership.

Work in Progress:

- Memory system architecture and implementation patterns

- Ontology framework with trait composition

- Integration examples across different industries

- Tool ecosystem for adopting the MIF standard

Check the MIF repository for current development status, ontology examples, and implementation guidance. Contributions to the trait library and industry ontologies help shape what’s possible.

Why This Matters

AI memory without ontology is like a library without the Dewey Decimal System. You can store books, but you can’t find the right one when you need it. You can’t understand how different books relate. You can’t build knowledge systematically.

The cognitive triad connects three components that each solve part of the problem:

- Persistent memory captures what happened and why

- Ontology provides semantic structure for interpreting memories

- Signal detection determines what’s worth capturing

Together, they create AI systems that remember, reason, and relate information consistently across sessions and domains.

For software engineers and architects, the implications are clear:

- Deterministic AI: Grounding memory and decisions in explicit ontologies replaces probabilistic hallucinations with reasoning

- Governance built-in: Audit trails, compliance rules, and access control are semantic constraints, not afterthoughts

- Cross-session continuity: AI assistants remember architectural decisions, design rationale, and lessons learned

- Token efficiency: Progressive disclosure enables rich context with 10-50x reduced token consumption

- Team knowledge transfer: Memories stored in git propagate to new team members alongside code

I built this because I was tired of explaining the same architectural decisions to AI assistants every time I started a new conversation. Now the system remembers. It understands context. It relates decisions to consequences.

The MIF standard documents this architecture so other teams can build compatible systems. The ontology examples demonstrate the concepts across domains.

AI memory and ontology aren’t optional add-ons. They’re foundational to trustworthy, maintainable, and effective AI systems.

Resources

- MIF Standard: github.com/zircote/MIF

- Memory System Implementation: github.com/zircote/mnemonic

- Cognitive Architecture: github.com/zircote/subcog

- Backstage.io Integration Examples: github.com/zircote/MIF/tree/main/ontologies/examples

Research References

- Baddeley, A. (2000). The episodic buffer: a new component of working memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 4(11), 417-423.

- Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology.

- Green, D. M., & Swets, J. A. (1966). Signal Detection Theory and Psychophysics.

- Peterson, L. R., & Peterson, M. J. (1959). Short-term retention of individual verbal items. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 58(3), 193-198.

- Baddeley, A. D., & Hitch, G. (1974). Working memory. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 8, 47-89.