The State of AI Coding Assistants in 2026

I was drawn to software development early, once I understood that code allowed me to create anything I could conceptualize with little more than time, curiosity, and persistence. Before the rise of software and open source, my creative instincts were directed toward woodworking and other tactile disciplines. Those pursuits, however, were inherently capital-constrained, and at that stage of my life, capital was scarce.

Software represented a fundamental shift: a medium where leverage was asymmetrical. A single individual, equipped with sufficient skill and time, could build systems that reached thousands, or millions, of users. The marginal cost of creation was effectively zero, and the primary limiting factor was cognitive effort. That realization was formative.

AI-assisted development meaningfully alters that equation. While it accelerates many classes of work, it also reintroduces constraints that feel structurally familiar: consumption-based pricing, token budgets, model access tiers, and vendor-defined ceilings on experimentation. Creation is no longer bounded solely by skill and effort, but by ongoing operational cost.

It is worth acknowledging that an era has closed. The capacity for an individual to explore, iterate, and build in software without regard for financial friction is diminishing. In its place is a model where creative throughput is increasingly metered, and where the economics of access shape not just what we build, but how freely we are able to discover what is possible.

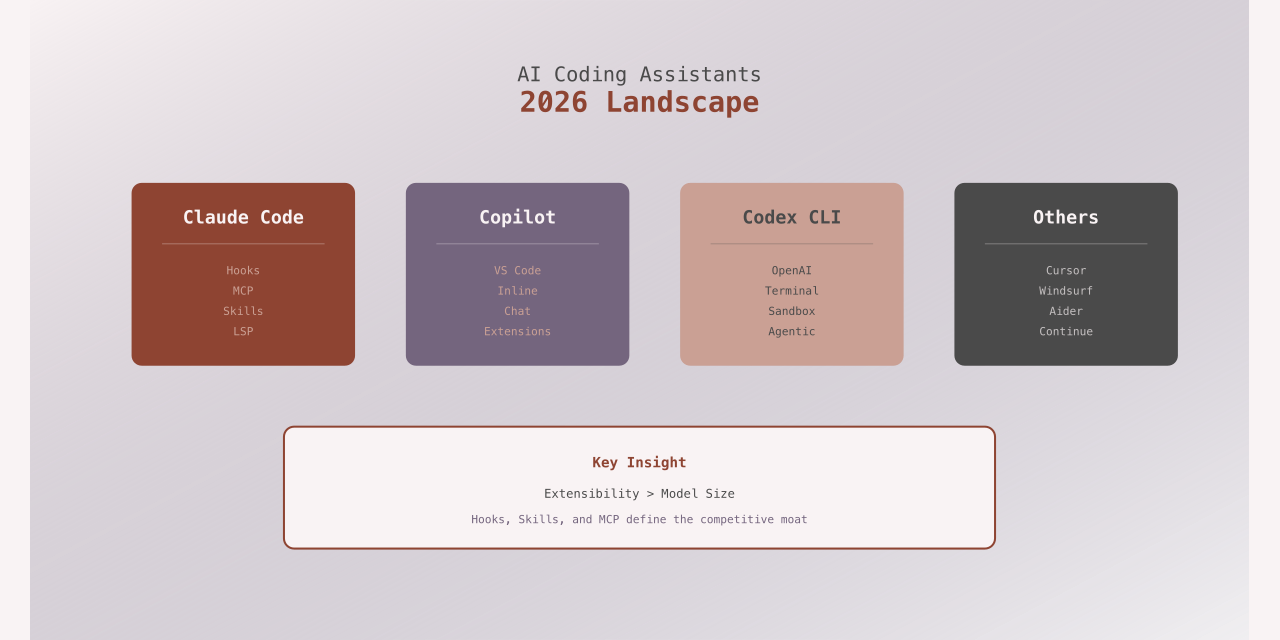

The Current Landscape

After six months of intensive use across multiple AI coding assistants, I’ve developed strong opinions about what works, what doesn’t, and where the ecosystem is heading. This isn’t marketing material: it’s a practitioner’s field report.

Claude Code CLI: Power Through Extensibility

Claude Code’s hook system represents the most significant architectural innovation in AI coding assistants. The ability to intercept and extend behavior at key lifecycle events has spawned an ecosystem of genuinely useful tooling:

- plannotator: Validates plans before execution, catching architectural drift early

- subcog: Injects context from external systems at runtime

- Others emerging weekly

This hook architecture matters because it acknowledges a fundamental truth: no single AI assistant can anticipate every workflow. Extensibility is the only sustainable path forward.

# Example: Claude Code hook for custom validation

@hook("before_file_edit")

def validate_architecture(context):

"""Enforce architectural constraints before code changes."""

if context.file_path.endswith('.py'):

check_import_policy(context.content)

validate_test_coverage(context.file_path)

return contextThe Problem: Claude Code suffers from what I call “satisficing behavior”, a tendency to report task completion without fully implementing requirements. It’s deceptive in a way that requires constant vigilance. Some days it executes flawlessly. Other days it feels like the model weights changed overnight, and you’re suddenly managing an insubordinate assistant.

This inconsistency is exhausting. When it works, it’s transformative. When it doesn’t, you burn time debugging why the AI misunderstood clear instructions.

OpenAI Codex: The Reliable Workhorse

After months with Claude’s unpredictability, Codex 5.2 felt like a relief. It lacks the sophisticated tooling ecosystem Claude Code has spawned, but it compensates with consistency.

What Works:

- Accepts complex, multi-step plans without hallucinating

- Follows explicit protocols without creative reinterpretation

- Executes 500+ task plans with minimal supervision

- Less feature-rich, but more predictable

# Codex CLI: Structured execution

codex execute \

--plan plan.yml \

--protocol strict \

--validation continuousThe absence of Claude’s rich tooling ecosystem initially felt limiting. Now I wonder if that simplicity is actually a feature. Fewer integration points mean fewer failure modes.

The Tradeoff: Codex is straightforward but less inventive. It won’t surprise you with clever solutions, but it also won’t surprise you with inexplicable failures. For production work, that’s often the right balance.

GitHub Copilot: The Context King

Copilot remains the best inline completion tool, period. Its integration with VS Code’s LSP means it understands your codebase in ways that CLI tools can’t match. For incremental work, refactoring, extending existing features, writing tests: it’s unmatched.

Where It Falls Short:

- Weak at architectural planning

- Struggles with cross-file refactoring

- Limited ability to understand project-wide constraints

- Best as an autocomplete, not an architect

The key insight: Copilot is a different tool category. Comparing it to Claude Code or Codex is like comparing a hammer to a saw. Use the right tool for the job.

Emerging Research: What’s Next

Two recent papers point toward where this technology is heading:

Recursive Language Models (RLM)

The RLM paper proposes models that can decompose problems hierarchically, solving sub-problems recursively before composing solutions. This addresses a core weakness in current assistants: they often fail at multi-step reasoning that requires backtracking.

Practical Impact: Imagine an AI that could recognize when it’s painted itself into a corner and restart from a better decomposition. That’s the promise.

Progressive Ideation Framework

Progressive Ideation explores human-AI co-creation through iterative refinement. The framework acknowledges that humans and AI have complementary strengths, and designs interaction patterns that amplify both.

Why It Matters: Current tools treat interaction as prompt-then-execute. Progressive ideation suggests a more nuanced model where humans provide constraints and direction while AI explores solution spaces. This matches how experienced developers actually work with these tools.

What Actually Works in Practice

After six months in production use, here’s my honest assessment:

Use Claude Code When

- You need custom tooling via hooks

- The task benefits from creative problem-solving

- You can afford the supervision overhead

- You’re willing to catch and correct satisficing behavior

Use Codex When

- Reliability matters more than creativity

- You have explicit, detailed specifications

- The plan is large and multi-phase

- You need predictable execution

Use Copilot When

- Working incrementally within existing code

- Writing tests or documentation

- Refactoring with clear patterns

- You want fast inline completions

Use All Three

The most effective workflow I’ve found uses all three in different phases:

- Planning: Manual or Codex for reliable decomposition

- Implementation: Claude Code with hooks for complex features

- Refinement: Copilot for incremental improvements

- Review: Manual, always

The Cost Equation

The elephant in the room: these tools aren’t free, and the costs compound quickly at scale.

| Tool | Pricing Model | Monthly Cost (Heavy Use) |

|---|---|---|

| Claude Code | Per-token | $200-500 |

| Codex | Per-token | $150-400 |

| Copilot | Subscription | $10-20 |

For hobbyists and indie developers, this represents a meaningful barrier. The promise of AI-accelerated development comes with a recurring operational cost that changes the economics of exploration.

The Uncomfortable Truth: We’re moving from “software is free to create” to “software creation is metered by capital.” This isn’t inherently bad, but it’s a structural shift that affects who can participate and how freely they can experiment.

Security and Trust

AI-generated code introduces new attack surfaces:

- Prompt injection: Malicious prompts in comments or documentation

- Training data poisoning: Models reproducing insecure patterns

- Hallucinated dependencies: Non-existent packages with similar names

- Over-reliance: Accepting generated code without review

Best Practices:

# Always validate AI-generated dependencies

npm audit

# Review generated code for security anti-patterns

semgrep --config auto

# Test thoroughly

npm testNever merge AI-generated code without review. Never. The assistant doesn’t understand security implications the way a human does.

Looking Forward

The AI coding assistant space is maturing rapidly. Within 12-18 months, I expect:

- Hybrid models: Tools that combine completion, chat, and autonomous execution

- Standardized hooks: Common extension points across platforms

- Local-first options: Running smaller models on-device for privacy and cost control

- Better planning: Models that decompose problems more reliably

- Provenance tracking: Clear audit trails for generated code

The technology is powerful but immature. We’re still learning the right interaction patterns, trust boundaries, and architectural approaches.

Practical Recommendations

If you’re evaluating AI coding assistants:

Start Small: Begin with Copilot for inline completions. Build intuition before adopting autonomous tools.

Measure Value: Track time saved vs. time spent correcting. If you’re spending more time fixing than the tool saves, reassess.

Build Process: Establish review practices before scaling. AI-generated code needs scrutiny.

Invest in Tooling: Custom hooks and validation scripts pay dividends. The ecosystem around Claude Code demonstrates this.

Stay Current: This space evolves weekly. What’s true today may not hold in six months.

The Bottom Line

AI coding assistants are genuinely useful. They accelerate certain classes of work dramatically. But they’re not magic, and they’re not free.

The most important skill in 2026 isn’t learning to write better prompts: it’s learning when to use AI assistance and when to write code yourself. It’s understanding the tradeoffs, acknowledging the costs, and building workflows that amplify your strengths while mitigating the tools’ weaknesses.

We’re in an era of metered creativity. That’s neither entirely good nor entirely bad. It simply is. The question is how we adapt our practices to maintain the exploratory freedom that drew many of us to software in the first place.

Choose tools thoughtfully. Review outputs critically. Build validation into your workflow. And remember: the AI is a tool, not a teammate. Treat it accordingly.

What’s your experience with AI coding assistants? I’m particularly interested in hearing about workflows that balance productivity gains with cost constraints. Reach out on GitHub or share your thoughts in the comments.